India's Expanding City of Widows

Over the last two years, the Sun has run numerous articles about the plight of the widows in Vrindavan Dhama. In August 2005, the issue gathered steam with the release of a film entitled Shwet - White Rainbow, which was nationally released in India. The movie exposed the horrible treatment dealt to widows in India.

Earlier this year, producer Deepa Mehta released "Water", the third in her elemental trilogy of films. Like White Rainbow, Water showcased the plight of widows in India. Shot amidst tremendous political resistance in Varnasi, the film was shut down by angry mobs. Mehta eventually filmed it secretly in Sri Lanka.

Over the last year, this issue has been slowly moving to the forefront of western social conscience, with pop musicians and movie superstars getting in on the action. Since high-profile British businessman Raj Loomba declared June 23 as International Widows Day, Vrindavan has been visited by the likes of Yoko Ono and Madonna.

Yesterday, the issue of the maltreatment of widows in Vrindavan surfaced yet again, this time on the front page of CNN, in an article entitled.

Commenting on the CNN article, AHN writer Linda Young reported, "It is believed that 15,000 Hindu widows live on the streets of Vrindavan, India, nicknamed "city of widows." Many of them are poor, hungry and homeless. The women are from across India. they went to Vrindavan after their husbands died because society, including their own families, shunned them. Forbidden to remarry and marginalized by a society that places no value on widows, the women are often called the living dead.

Although it is believed that a widow who dies in Vrindavan will be freed from the cycle of numerous lives and deaths, it is not religion that causes the widow's banishment there. It is economics. The women are seen as a drain on the finances of their family.

Widows are required to shave their heads and wear white robes. Widows are traditionally ostracized in India, although not all of them are forced to leave their home.

But for those who are, those who arrive in Vrindavan without any money primarily live on the streets begging if no one will take them in. Often they don't eat every day and many of the elderly women curl up to sleep on stone verandas outside temples or on the streets.

One widow related what happened to her after her husband of 50 years died.

"My son tells me: 'You have grown old. Now who is going to feed you? Go away,'" she said, according to CNN. As the 70-year-old mother's eyes filled with tears she said, "What do I do? My pain had no limit."

At the very least there is social humiliation when a woman is widowed. She is told not to attend weddings because her presence is bad luck, says a widow who is working to change customs.

"Generally all widows are ostracized," Dr. Mohini Giri said, according to CNN. "An educated woman may have money and independence, but even that is snatched away when she becomes a widow. We live in a patriarchal society. Men say that culturally as a widow you cannot do anything: You cannot grow your hair, you should not look beautiful."

Giri has formed an organization called the Guild of Service to help destitute women and children. It has established homes where the widows live. There the women wear brightly colored clothing and grow their hair long.

Widows have never had an easy time in India. Before 1929, when officials banned the practice, widows in many parts of India were encouraged to commit Sati, the act of throwing themselves on their husband's burning funeral pyre and burning to death. Although the practice was banned by the government, Sati deaths were reported in India as recently as the 1980s."

In the one devotee posted this message entitled "Vrindavan's Widows: Son To Mother, You Are Too Old, Go Away", in which s/he brings the issue squarely into ISKCON's camp. As Srila Prabhupada's representatives in the Holy Dhama, we can expect the devotees to increasingly question whether we have a responsibility to get involved in the issue, which is bringing such negative focus to bear on Vrindavan Dhama.

"The top story on CNN.com -- beating out the arrest of Al Gore III and a new video from Al Qaeda second-in-command Ayman al-Zawahiri -- is this story on shunned widows awaiting death in Vrindavan.

As expected, readers are horrified by the backwards and inhumane treatment of these women -- 40 million in India, and 15 thousand on the streets of Vrindavan. Some blame Hinduism or the Vedic scriptures for this cruel practice. Others say that it is all about money and greed.

As Gaudiya Vaisnavas we hold Vrindavan to be sacred ground -- Lord Krishna's own abode. How do we reconcile that belief with the adharmic treatment of thousands that is purportedly happening there? Can we or should we do something about it? Or is this just a case of a pro-Westernized, anti-Hindu media slant, hyping a story where there really is none? Is this an opportunity for ISKCON to be proactive and take a stance, or an embarrassment that we should hope just goes away?

In any event, one thing is clear: even if we don't have the answers on this one, we must be willing to face the questions. - Source: ISKCON Communications

Here is the beginning of the article on Vrindavan Widows from CNN:

"Ostracized by society, India's widows flock to the holy city of Vrindavan waiting to die. They are found on side streets, hunched over with walking canes, their heads shaved and their pain etched by hundreds of deep wrinkles in their faces.

Hindu widows are shunned from society when their husbands die, not for religious reasons, but because of tradition -- and because they're seen as a financial drain on their families."

In another instacne we read this from that article.

"Biswas speaks with a strong voice, but her spirit is broken. When her husband of 50 years died, she was instantly ostracized by all those she thought loved her, including her son.

"My son tells me: 'You have grown old. Now who is going to feed you? Go away,' " she says, her eyes filling with tears. "What do I do? My pain had no limit."

This is sad and the government of India should work very hard with the society to eliminate these types of very negative instances. So that the people never know what it means to be a Vrindavan Widow."

Surina Devi, a matronly 70-year-old in a brown crepe sari, had a so-so life, she says, until her shopkeeper husband died four years ago. For reasons she is unable or loath to explain, the former housewife from a rural village near Patna, in Bihar, was left with "nothing, nothing."

So Ms. Devi did what poor Indian widows have been doing for centuries: She packed a bag and made her way to Vrindavan, a holy town in northern India that is also known as the City of Widows. After a night sleeping on the pavement, she found a bed in an crowded ashram - a house of prayer - for widows, where she says she will spend the rest of her life.

But it's not much of a life. And this town where 16,000 women dress in white - the colour of death - is growing, according to a new report. The survey, published last month by the United Nations Development Fund for Women and the Delhi-based Guild of Service, an Indian charity for widows, illuminates the harsh realities for Vrindavan's widows.

It reveals that 40 percent of women here were married before the age of 12. A third were so impoverished that they traveled to Vrindavan without a train ticket. But perhaps the more startling fact is that despite India's economic ascension and its increasing exposure to global cultural forces, the report offers anecdotal evidence that the number of widows flocking to the town is on the rise.

Nearly a millennium after the Skanda Purana, a Hindu text, described widows as "more inauspicious than all other inauspicious things," many husbandless women in India still live as impoverished pariahs, shunned by their families and society when their husbands die. According to the report's author, it is poverty and a lack of independence, not spiritual devotion, that has turned the City of Widows into a kind of boomtown.

In many cases, the pressures of modern Indian life have exacerbated the brutality of tradition, as an increasing number of Indian children refuse to care for their parents, male or female, says Mittal Patel, manager of a government-funded ashram in Vrindavan. "Children are less supportive than they used to be," says Ms. Patel. If this is so, few of the mothers now living in Vrindavan will admit it.

"Only yesterday, my son telephoned and said he is coming to fetch me," says Chavi Das, a tiny, elderly woman in a canary-yellow sari, as she squats on the courtyard veranda of the Aamir Bari ashram with a dozen other elderly women. Rukmani, who goes by one name and is "60 or 70," shakes her head vigorously when she says she has no children. But a moment later, she mumbles bitterly that she is a "hot-headed woman" and it is her fault that things went wrong with her daughter-in-law.

Widows have come to Vrindavan since the 16th century, hoping that Sri Krsna will grant them moksha, or freedom, from the cycle of birth and rebirth. But more than that, they hope that the material benefits of Vrindavan, with its 5,000 temples and numerous alms-giving ashrams, will allow them to survive a little longer in this life.

As poor as she is, Rukmani is comparatively well off. At Aamir Bari, the 110 residents are encouraged to wear the brightly colored saris of their former lives. They watch television, cook, and gossip. More important, Aamir Bari is the only ashram in Vrindavan that provides three meals a day. Elsewhere, widows must earn their bread by singing in temples.

At 3 pm in the centre of town, more than 1,000 women in grubby white saris shuffle into the dimly lit hall of a temple for the second of two lengthy hymn-singing shifts. First they queue up to receive a small plastic token from the temple. Then they sit in rows on the floor, facing a shrine to Krishna and Radha, his beautiful lover. Several women are lying down. One, with trembling hands, unfolds a sheet of waterproof plastic and carefully arranges it beneath her.

And then the singing begins: 3-1/2 hours of "Hare Rama, Hare Krishna" to the roll of drums and clashing of cymbals. After the song, the women slowly rise and line up again, this time exchanging each coupon for three rupees (about 7 cents) from the temple's cashier. "It's a kind of torture, sitting there for hours," says Maduri Devi, a feisty white-haired resident at the government-funded Meera Sahbhagini Mahila ashram, where she sits on a charpoy, girlishly swinging her legs. Though Ms. Devi and her 300-plus fellow residents are given a daily food ration, it is not enough to live on, says the widow of a homeopathic doctor from Patna in Bihar. "I have lived a much better life than this," she says proudly. "But many of the women here are poorer than me and for them, I don't think this life is so bad." [Christian Science Monitor].

Earlier this year, producer Deepa Mehta released "Water", the third in her elemental trilogy of films. Like White Rainbow, Water showcased the plight of widows in India. Shot amidst tremendous political resistance in Varnasi, the film was shut down by angry mobs. Mehta eventually filmed it secretly in Sri Lanka.

Over the last year, this issue has been slowly moving to the forefront of western social conscience, with pop musicians and movie superstars getting in on the action. Since high-profile British businessman Raj Loomba declared June 23 as International Widows Day, Vrindavan has been visited by the likes of Yoko Ono and Madonna.

Yesterday, the issue of the maltreatment of widows in Vrindavan surfaced yet again, this time on the front page of CNN, in an article entitled.

Commenting on the CNN article, AHN writer Linda Young reported, "It is believed that 15,000 Hindu widows live on the streets of Vrindavan, India, nicknamed "city of widows." Many of them are poor, hungry and homeless. The women are from across India. they went to Vrindavan after their husbands died because society, including their own families, shunned them. Forbidden to remarry and marginalized by a society that places no value on widows, the women are often called the living dead.

Although it is believed that a widow who dies in Vrindavan will be freed from the cycle of numerous lives and deaths, it is not religion that causes the widow's banishment there. It is economics. The women are seen as a drain on the finances of their family.

Widows are required to shave their heads and wear white robes. Widows are traditionally ostracized in India, although not all of them are forced to leave their home.

But for those who are, those who arrive in Vrindavan without any money primarily live on the streets begging if no one will take them in. Often they don't eat every day and many of the elderly women curl up to sleep on stone verandas outside temples or on the streets.

One widow related what happened to her after her husband of 50 years died.

"My son tells me: 'You have grown old. Now who is going to feed you? Go away,'" she said, according to CNN. As the 70-year-old mother's eyes filled with tears she said, "What do I do? My pain had no limit."

At the very least there is social humiliation when a woman is widowed. She is told not to attend weddings because her presence is bad luck, says a widow who is working to change customs.

"Generally all widows are ostracized," Dr. Mohini Giri said, according to CNN. "An educated woman may have money and independence, but even that is snatched away when she becomes a widow. We live in a patriarchal society. Men say that culturally as a widow you cannot do anything: You cannot grow your hair, you should not look beautiful."

Giri has formed an organization called the Guild of Service to help destitute women and children. It has established homes where the widows live. There the women wear brightly colored clothing and grow their hair long.

Widows have never had an easy time in India. Before 1929, when officials banned the practice, widows in many parts of India were encouraged to commit Sati, the act of throwing themselves on their husband's burning funeral pyre and burning to death. Although the practice was banned by the government, Sati deaths were reported in India as recently as the 1980s."

In the one devotee posted this message entitled "Vrindavan's Widows: Son To Mother, You Are Too Old, Go Away", in which s/he brings the issue squarely into ISKCON's camp. As Srila Prabhupada's representatives in the Holy Dhama, we can expect the devotees to increasingly question whether we have a responsibility to get involved in the issue, which is bringing such negative focus to bear on Vrindavan Dhama.

"The top story on CNN.com -- beating out the arrest of Al Gore III and a new video from Al Qaeda second-in-command Ayman al-Zawahiri -- is this story on shunned widows awaiting death in Vrindavan.

As expected, readers are horrified by the backwards and inhumane treatment of these women -- 40 million in India, and 15 thousand on the streets of Vrindavan. Some blame Hinduism or the Vedic scriptures for this cruel practice. Others say that it is all about money and greed.

As Gaudiya Vaisnavas we hold Vrindavan to be sacred ground -- Lord Krishna's own abode. How do we reconcile that belief with the adharmic treatment of thousands that is purportedly happening there? Can we or should we do something about it? Or is this just a case of a pro-Westernized, anti-Hindu media slant, hyping a story where there really is none? Is this an opportunity for ISKCON to be proactive and take a stance, or an embarrassment that we should hope just goes away?

In any event, one thing is clear: even if we don't have the answers on this one, we must be willing to face the questions. - Source: ISKCON Communications

Here is the beginning of the article on Vrindavan Widows from CNN:

"Ostracized by society, India's widows flock to the holy city of Vrindavan waiting to die. They are found on side streets, hunched over with walking canes, their heads shaved and their pain etched by hundreds of deep wrinkles in their faces.

Hindu widows are shunned from society when their husbands die, not for religious reasons, but because of tradition -- and because they're seen as a financial drain on their families."

In another instacne we read this from that article.

"Biswas speaks with a strong voice, but her spirit is broken. When her husband of 50 years died, she was instantly ostracized by all those she thought loved her, including her son.

"My son tells me: 'You have grown old. Now who is going to feed you? Go away,' " she says, her eyes filling with tears. "What do I do? My pain had no limit."

This is sad and the government of India should work very hard with the society to eliminate these types of very negative instances. So that the people never know what it means to be a Vrindavan Widow."

So Ms. Devi did what poor Indian widows have been doing for centuries: She packed a bag and made her way to Vrindavan, a holy town in northern India that is also known as the City of Widows. After a night sleeping on the pavement, she found a bed in an crowded ashram - a house of prayer - for widows, where she says she will spend the rest of her life.

But it's not much of a life. And this town where 16,000 women dress in white - the colour of death - is growing, according to a new report. The survey, published last month by the United Nations Development Fund for Women and the Delhi-based Guild of Service, an Indian charity for widows, illuminates the harsh realities for Vrindavan's widows.

It reveals that 40 percent of women here were married before the age of 12. A third were so impoverished that they traveled to Vrindavan without a train ticket. But perhaps the more startling fact is that despite India's economic ascension and its increasing exposure to global cultural forces, the report offers anecdotal evidence that the number of widows flocking to the town is on the rise.

Nearly a millennium after the Skanda Purana, a Hindu text, described widows as "more inauspicious than all other inauspicious things," many husbandless women in India still live as impoverished pariahs, shunned by their families and society when their husbands die. According to the report's author, it is poverty and a lack of independence, not spiritual devotion, that has turned the City of Widows into a kind of boomtown.

In many cases, the pressures of modern Indian life have exacerbated the brutality of tradition, as an increasing number of Indian children refuse to care for their parents, male or female, says Mittal Patel, manager of a government-funded ashram in Vrindavan. "Children are less supportive than they used to be," says Ms. Patel. If this is so, few of the mothers now living in Vrindavan will admit it.

"Only yesterday, my son telephoned and said he is coming to fetch me," says Chavi Das, a tiny, elderly woman in a canary-yellow sari, as she squats on the courtyard veranda of the Aamir Bari ashram with a dozen other elderly women. Rukmani, who goes by one name and is "60 or 70," shakes her head vigorously when she says she has no children. But a moment later, she mumbles bitterly that she is a "hot-headed woman" and it is her fault that things went wrong with her daughter-in-law.

Widows have come to Vrindavan since the 16th century, hoping that Sri Krsna will grant them moksha, or freedom, from the cycle of birth and rebirth. But more than that, they hope that the material benefits of Vrindavan, with its 5,000 temples and numerous alms-giving ashrams, will allow them to survive a little longer in this life.

As poor as she is, Rukmani is comparatively well off. At Aamir Bari, the 110 residents are encouraged to wear the brightly colored saris of their former lives. They watch television, cook, and gossip. More important, Aamir Bari is the only ashram in Vrindavan that provides three meals a day. Elsewhere, widows must earn their bread by singing in temples.

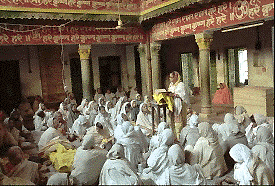

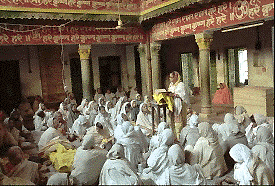

Bhagwan Bhajan Ashram

At 3 pm in the centre of town, more than 1,000 women in grubby white saris shuffle into the dimly lit hall of a temple for the second of two lengthy hymn-singing shifts. First they queue up to receive a small plastic token from the temple. Then they sit in rows on the floor, facing a shrine to Krishna and Radha, his beautiful lover. Several women are lying down. One, with trembling hands, unfolds a sheet of waterproof plastic and carefully arranges it beneath her.

And then the singing begins: 3-1/2 hours of "Hare Rama, Hare Krishna" to the roll of drums and clashing of cymbals. After the song, the women slowly rise and line up again, this time exchanging each coupon for three rupees (about 7 cents) from the temple's cashier. "It's a kind of torture, sitting there for hours," says Maduri Devi, a feisty white-haired resident at the government-funded Meera Sahbhagini Mahila ashram, where she sits on a charpoy, girlishly swinging her legs. Though Ms. Devi and her 300-plus fellow residents are given a daily food ration, it is not enough to live on, says the widow of a homeopathic doctor from Patna in Bihar. "I have lived a much better life than this," she says proudly. "But many of the women here are poorer than me and for them, I don't think this life is so bad." [Christian Science Monitor].

--~--~---------~--~----~------------~-------~--~----~

To register to this vallalargroups, and Old Discussions http://vallalargroupsmessages.blogspot.com/

To change the way you get mail from this group, visit:

http://groups.google.com/group/vallalargroups/subscribe?hl=en

அருட்பெருஞ்ஜோதி அருட்பெருஞ்ஜோதி

தனிப்பெருங்கருணை அருட்பெருஞ்ஜோதி

எல்லா உயிர்களும் இன்புற்று வாழ்க

-~----------~----~----~----~------~----~------~--~---

No comments:

+Grab this

Post a Comment